Alaska has been my ski destination of choice almost every spring for the past 13 seasons. The access, deep dependable snowpacks, a wide variety of terrain and objectives, and affordability can’t be beat. I’ve camped and explored in seven different ranges, skied off Denali, pioneered first descents in the Revelations and filmed steep spines in Haines. Those were some of the successful trips and the more visits I make the longer the list of things I’d like to ski grows. It’s not all sunshine and rainbows, however. I’ve ended up tent-bound for eight days with as many feet of snow falling on us. I’ve been stuck in Talkeetna for nine-day stretches where no planes flew in or out of the glaciers and I never even touched snow. Skiing in Alaska is feast or famine with major ups and downs, but the highs are very high, and the lows are forgotten with time. What I’ve learned is that you need to keep a very wide range of options open, remain flexible with plans—and most importantly—just keep showing up.

Image: Noah Howell

In May 2018, I returned, this time with Teton legend and guide, Adam Fabrikant. We were casting a wide net in terms of our objectives, as almost all of Alaska was in play. After seeing the unsettled weather forecast across most of the state, we chose to fly into the popular Kahiltna base camp in the Alaska Range, which we were both very familiar with. Here, we could find plenty of good ski options at many different elevations and aspects to increase our chances of making turns down something interesting.

Our main objective became the 11,000-foot Archangel Ridge on Mount Foraker. We paid extra for a fly-over on the way into the range. On inspection the line was very icy and not holding snow, so we changed our focus. From the sky however, we caught a glimpse of the Ramen Couloir on Mount Hunter. The base of it was poking out of the clouds and there didn’t appear to be any avalanche debris or runnels, which was a good sign. This quickly became the main object of our attention and affection. Normally it would be too late in the year to consider this lower elevation south facing line, but May had been one hell of a snowy month and the storms had just now abated.

Image: Adam Fabrikant

With continued mixed weather in the forecast we set up camp near the landing strip and got to know the snowpack by skiing a fun south facing line off of peak 12,200. The next evening, we skied the east ridge on Mount Frances after 6-8” of new snow fell. That night the storm lifted as we skied back to our tent. The late sun was bursting all over Mount Hunter like a sign from the gods. We packed up three days of food and fuel and left Kahiltna base camp around 1 a.m. to check out the Ramen Couloir route.

At 14,573 in elevation, Begguya (Denali’s child, in its native tongue), or Mount Hunter, is the 3rd tallest peak in the Alaska Range and the 10th in the state. Of the three tallest, Hunter is considered the most difficult peak to climb and the hardest 14,000-foot peak in the good old USA. It only sees a handful of attempts and very few summits each winter. Most are via the highly technical Moonflower Buttress, or the less difficult, but very long West Ridge. The mountain sees even less skier traffic and has only been descended by one route, the Ramen Couloir. In 2003, a crew with Lorne Glick and Andrew McLean pioneered this complex 8,500-foot route. Since then two other parties have succeeded on it. There have been a few unsuccessful attempts at other routes, including one by Adam Fabrikant, Billy Haas and a top-notch gang who worked on the East Ridge, but were turned back by the severe cornicing.

Image: Noah Howell

To get to the base of the couloir Adam and I traveled down the main Kahiltna glacier for several miles and hooked a left up the unnamed branch. It probably doesn’t have a name because it sees so little traffic. It sees so little traffic because there are few people stupid enough to want to ski Mount Hunter. One of the reasons there are few people stupid enough to want to ski Mount Hunter is because the most dangerous part is just getting to the base. It requires guessing your way through an enormous Tim Burton-esque ice-fall. If you’re going to do stupid things you’ve got to be smart about it. We consciously chose to navigate in the middle of the night so the frozen towers and bridges might stay put. Luckily, we chose well and only had to backtrack a few times and climb one short vertical section.

Around 6 a.m. we set up a tent near 8,000 feet, within a few hundred yards of the couloir’s base. The sunny day was spent relaxing, hydrating, eating and staring up at the line. Our view was partly in and out of the clouds, but we caught full glimpses from time to time. Ski mountaineering consists of skiing, yes, but most of the time is actually spent in speculating. What will the snow be like? Where is the crux? How much time will it take? How much food should we bring? How much water? Which tools? What layers? When do we start? What time will be the best skiing? Normally this dialogue between partners is a vital part of the process and helps abate some of our concerns, but for some reason the mental exercises took their toll this time and I got worked into an anxious state. I opened up to Adam about my concerns and he helped talk it out. We started booting up the chute and the ability to move dispersed my fear and turned all those question marks into exclamation points.

The Ramen Couloir is a 3,500-foot, 50+ degree, south facing chute that gains the west ridge and follows it to the summit. We made good time taking turns breaking trail in the yet to freeze crust. Near the top we made a variation from the original route by cutting right through some large seracs and gaining the ridge. This was the steepest and most exposed part of the route by far, but the snow was firm and held potential for transitioning into good corn. It was nice passing through in the relative darkness and not getting to fully appreciate the exposure, but that would come later.

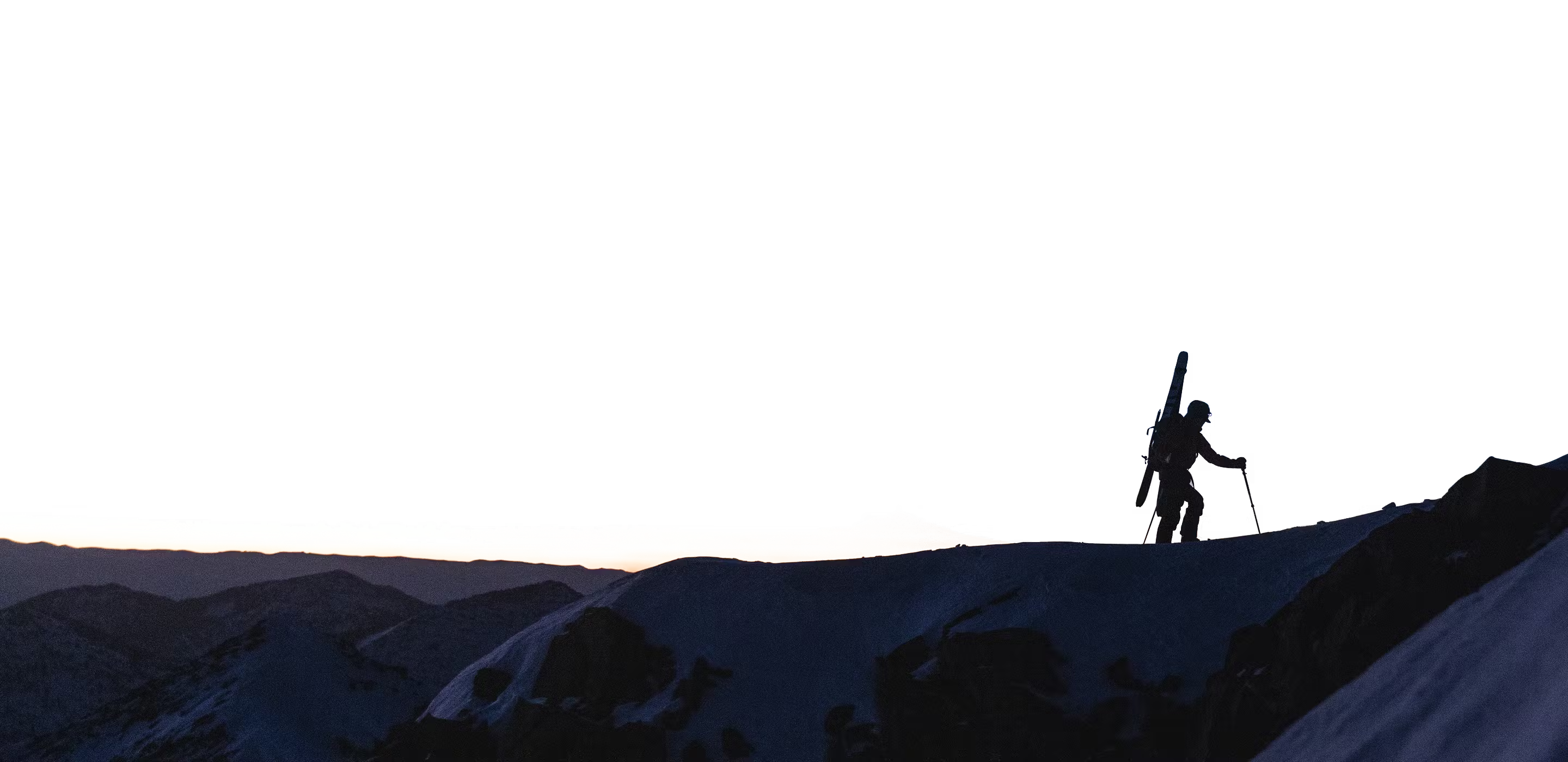

The sun doesn’t fully set this time of year, providing prolonged sunrises and sunsets. We tried to keep moving along the ridge with two difficulties, breaking trail in deep snow and not stopping every other step to take in the subtle light casting gently on the endless alpine all around and below us. I’m not sure I’ve had a more magical climb on any mountain in any range. Adam was moving well and faster than me. He was cold and didn’t want to stop to refuel so we kept moving. Most of the ridge we were able to cover by skinning and then we put on billy goat plates for the occasional steep sections. The final bump to the summit was icy and near 50 degrees. We engaged the slope with both ice tools and crampons, protected with a few screws and then we were able to easily walk the final few hundred feet to the summit.

Image: Adam Fabrikant

Clear days in Alaska are rare—clear days without any wind are maybe doubly rare. This day was both. We sat exhausted and in awe at where we were. Denali had some clouds covering the summit, but almost everywhere else was visible. Rugged white mountains … everywhere. Real men talk about feelings, and we tried to put words around the unspeakable, but they all felt small and inadequate, like us. Today was special, spiritual even—whatever that means—maybe working through all the fears made it more so.

The sun was gaining warmth and I didn’t want to move from our bliss, but it was time. Those sun rays were slowly warming up our couloir and we needed to beat the heat.

The great part about skiing, is the skiing! It’s such a fun and easy way to cover ground. Instead of trudging down, we now got to slide and glide, making short work to descend what had taken us 10 hours to climb.

The initial turns were great on the mellow summit ridge. Two short rappels got us off of the steep and icy face. From there it was smooth, soft sailing down the ridge. We stuck close to our uphill track so we could avoid falling into any new unseen crevasses. The top of the Ramen opened up and I slowly worked in first, feeling it out. The slope was over 50 degrees and the snow was perfect edgy corn. No place to fuck up as we worked our variation through the seracs and into the main chute. The steepness didn’t let up much and we worked smooth patches of corn in-between rock islands and jumbled piles of frozen debris. Adam shot ahead and I slowed down to milk the run, I didn’t want it to end. This continued right to the glacier and we both commented that it might be the most consistently steep pitch we’ve ever skied.

Images: Adam Fabrikant

That afternoon was another sunny one, and we dried out our gear and fed and watered the body. We needed to wait for the temps to drop before we could exit through the icefall. As we waited the mountains started unleashing large avalanches for our entertainment including some big wet slides down the Ramen.

That night we rolled back into Kahiltna base-camp late and slept hard, well into the next day. Adam had developed some blisters that seemed to be frostbite, not friction, after checking them out more closely. We checked in with the rangers and they confirmed it. Despite Adam’s ever-strong desire to keep skiing, we convinced him the best call was to return to town and take care of his feet before more damage was done. He reluctantly abided.

We hadn’t been on the glacier long, but we had skied three excellent lines and now it was time to go. I’d like to say our many years of experience in the mountains, good preparation, great communication and team dynamics and flexibility with plans allowed us to pull off a great line in one of the most incredible ranges on the planet. But the truth is also that we got lucky. After we left there was a continued spell of good weather, but then significant snowfall returned to the range and thwarted most parties and their plans. There were probably only a handful of days where summiting Mount Hunter was even possible, and we were there for one of them. As far as we know, in 2018, we were the only team to summit.

Image: Adam Fabrikant

I’ll be back next year, maybe just to sit in the coffee shop in Talkeetna watching it rain, or to be stuck in a tent while it snows, or maybe stand on top of something tall and get to ski down it. There is only one way to find out—and that’s to keep showing up.

--BD Athlete Noah Howell

Featured Gear