“The first mountain I ever climbed was walking from 770 to Asbury Park,” says Andrew King.

The 33-year-old climber, surfer, free diver, and explorer is reflecting on his upbringing in Detroit as a Black American.

“Walking to school every day, you didn’t know what was going to happen.”

King is sitting in his apartment in LA for this interview, candidly explaining his life over a Zoom call. He’s wearing a button up shirt, a sign of his professional career, and a BD beanie, hinting at his more adventurous side. The juxtaposition fits him well, which is telling, because from a young age, King has always attempted to navigate between worlds.

King grew up with a single mom in a rundown, crime heavy, section of Detroit City. He never had a father, and for him, that’s OK.

“I was raised by a village of people,” he says.

He credits his great grandparents, grandparents, mother, brother and others in the community for watching over him in what he calls a “turbulent environment.”

“We didn’t have a lot, but we had each other.”

There were early signs that King was going to challenge the status quo of his surroundings. He listened to Miles Davis and became a jazz fan. He loved school. And more importantly he constantly talked about going to college.

“When you’re someone who is trying to push past that glass ceiling, that’s not something the community wants to see,” says King. They say, ‘do you think you’re better than us?’”

That’s why his grandparents decided to adopt King and move him out of Detroit.

King’s grandfather Warren was a master sergeant in the United States Military, and along with his grandmother Darlene, King joined their household at 11 years old. They first moved to Snellville, Georgia, and it was then that King’s grandfather instilled a deep discipline that still fuels his training and life today.

“I remember him saying, ‘if you want to be good at something, you need to have discipline within yourself to do it.’”

King’s grandfather was “tough” on him, but in reflection, he attributes this to his success today.

The Georgia years for King were short lived, however.

“Someone in middle school called me the ‘n-word’ and I hit him,” remembers King. “I just knocked him straight out.”

His grandparents were concerned. King got suspended from school, though he remembers not really understanding why. And it was during his suspension when he was downstairs playing video games and his grandfather walked into the room.

“He goes, ‘I’m going to Europe.’ And I’m like, ‘OK, cool.’ And he says, ‘You’re also going to come with me.’”

King’s grandfather decided that going to school in Germany would introduce him more cultures, more people, and broaden his world views. He wanted King to become a global citizen not bound by the color of his skin.

It was as a high schooler in Germany, where King says he learned how to “be a human.” He learned the language and traveled extensively to compete in track in field. A talented sprinter, King brought the discipline he’d learned from his grandparents to running.

“I’m 5’4” so all I did was practice running every fucking day,” laughs King.

King broke records and medaled in high school, and it was his dedication to running that would eventually open doors to higher education.

But first he’d discover Hawaii.

At roughly 18 years old, King moved to his grandparents’ place on Ewa Beach, Oahu, where they’d been stationed. And to this day, Hawaii is what he considers home. King finally saw people of color participating in the sports he was interested in.

“In Hawaii, you can be brown and surf,” he says. “You still have to prove yourself, but not because the color of your skin.

King took to surfing and liked the aspect of “taking what you’re getting,” while reading waves in the ocean. He also started hiking the volcanoes and peaks of the islands when there weren’t any waves, gaining a love for seeking summits.

But the ocean and mountains would have to wait. King still had dreams to realize.

“I got into Moorehouse College and my family was ecstatic,” laughs King. The historically black men’s liberal art college in Atlanta, Georgia, is what King calls the “Harvard of black colleges.”

Yet, King had other plans. He was planning to go to the University of Maine.

“They were like, ‘you’re going to the whitest school in the entire United States?’”

King had received a track and field scholarship to be a D1 athlete at Maine. Which means that his grandparents wouldn’t have to pay for school if he chose that route. So that’s the path he took.

He studied Mass Communication and got a bachelor’s degree with a minor in Political Science. In between semesters he’d travel back “home” to Hawaii to surf and be in nature.

After college, King pursued graduate school in Boston at Lasell University for Integrated Marketing, and that’s when the climbing bug really took hold. He was 22 years old, and would spend all of his extra time, money, and energy on climbing mountains and surfing. He started with volcanoes, because he knew once he reached the top, he could come down and surf. After getting his master’s degree, King continued his outdoor pursuits while maintaining a job as a project manager at LEGO. When he wasn’t working, surfing, or climbing, he’d fly across the country to see his grandparents who were now retired to a farmhouse in Puyallup, Washington.

It was during this time when Andrew had the idea for The Between Worlds Project. He was 26 years old and traveling in a mining town in Taiwan to climb Mount Fuji. It was a chance encounter with a woman in a coffee shop that sparked the idea.

“She asked where I was from and I said, ‘America.’ And she said, ‘I’ve always wanted to go there,’ and I said, ‘well you should come sometime.’”

It dawned on King.

“That’s when it hit me that what I said was pretty ignorant. It would take so much more than this woman has to afford to do that.”

For King, he realized that we are all “between worlds.”

“From where we are born as ‘lottery tickets,’ like as a black man in Detroit, for example, or a woman in a mining town in Taiwan. Boom, that’s your lottery ticket. We’re all navigating the space of what’s under that glass ceiling and what’s above it. Over the years, what I’ve realized is The Between Worlds Project is moving between those two worlds—where we stand under the glass ceiling and seeing what’s above it.”

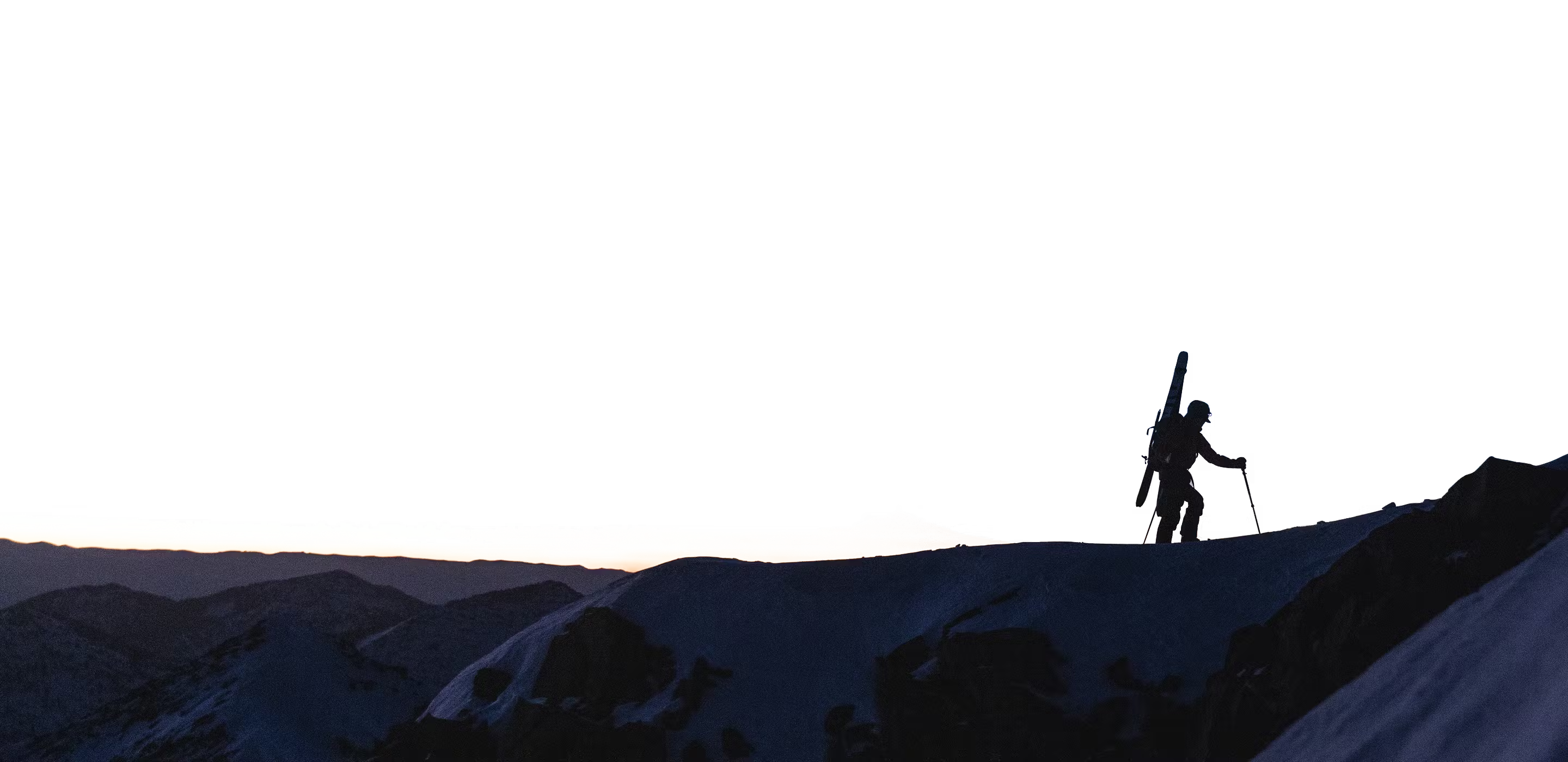

From that day on, King has been driven not to “conquer mountains,” but to seek out stories of struggle within the communities he travels to while attempting to climb the world’s 14 summits—the seven summits plus the seven tallest volcanoes. He’d be the first African American to reach all 14 summits, but to King, that’s not the overall goal.

“This project is about articulating those stories of people and their struggles while navigating that space and attempting to break through the glass ceiling.”

When King travels to climbing destinations, he also partners with nonprofits and individuals in the area that embody what he describes as a “positive change for tomorrow within nature, while combating racism, sexism, climate change, and economic limitations.”

Three years ago, King moved to LA to be closer to his grandparents and great grandmother Edna Reece while continuing to pursue The Between Worlds Project. He has 11 summits left, and as to be expected, the pandemic has slowed him down. King’s great grandmother passed away from complications of COVID-19 in April—a loss he’s still grieving from.

But the The Between World’s Project is a way to continue everything she and his grandparents taught him.

“That’s what it all comes down to. It wasn’t just traveling and taking me from one place to another. They were allowing me to see what the world is, and then build a life that would allow me to break through that glass ceiling.”

King’s next mission is to climb Denali. And when he reaches the summit, he wants to spread his great grandmother’s ashes there.

“I want her to rest in a place higher than where she began. Because that’s what she did for me.”

Follow Andrew and The Between Words Project here: thebetweenworldsproject.com

--Words: Chris Parker

--Images: Courtesy of Andrew King

FEATURED GEAR